Image © Jose & MidJourney

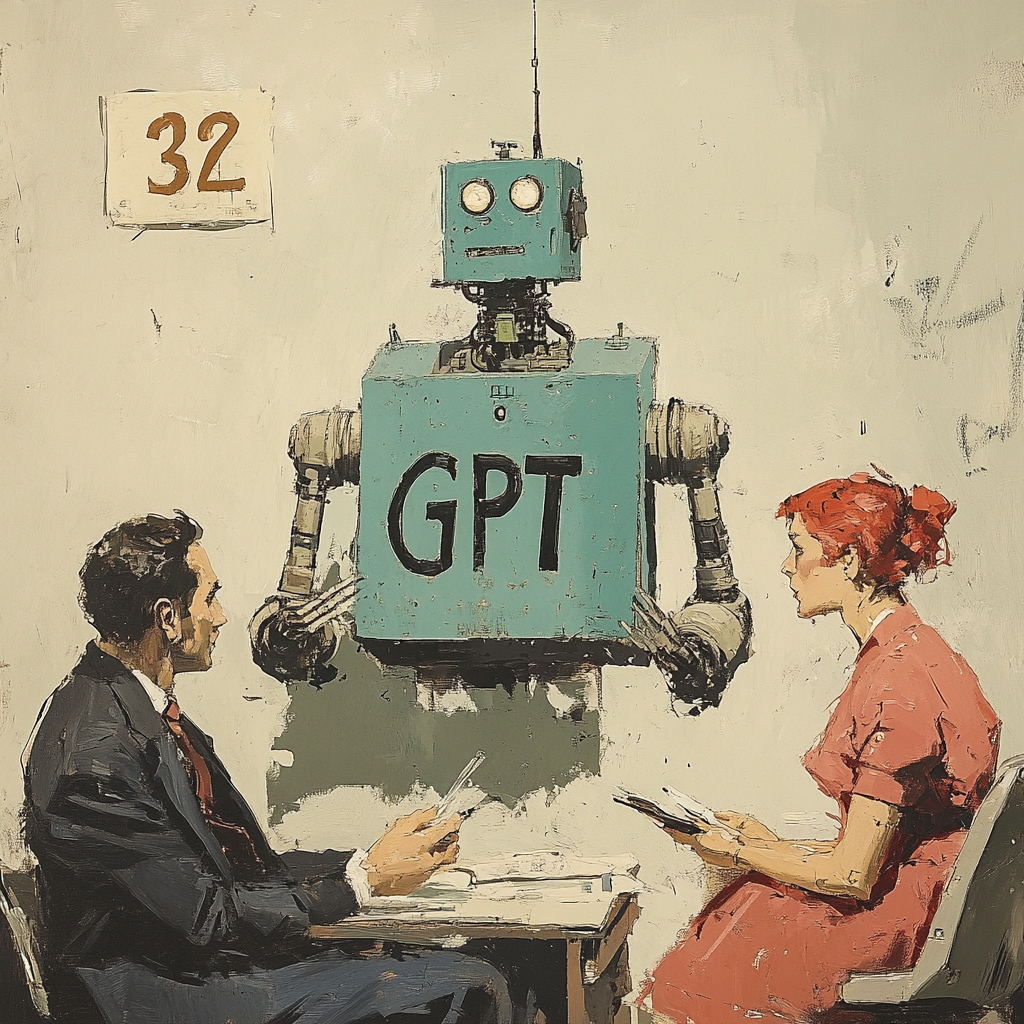

I come from a generation that had a bookshelf in the living room, among all the books and independently of what they were about, you’d find one or more dictionaries, and the ultimate prize used to be a collection of the Encyclopaedia Brittanica, a general knowledge ‘database’ first published in Scotland in 1768. Known for its scholarly approach and reliability, the articles were written by experts and scholars in various fields, and it was seen as a trusted reference source for everybody. These were leather bound collections of large books (32 volumes in last physical publication), organized alphabetically, prominently displayed as a sign of culture and education.

Above all, they served the purpose of argument broker between family and friends, whenever a discussion hit a certain point, there would always be someone that got up from the table and reached out to the right volume, search for the topic and page, and read out loud what it said. The good thing about it was the fact that it was final, undisputed, incomplete perhaps but always definitive. Many a fights, injuries and potential deaths were avoided by the consultation of the Encyclopaedia, you might not have liked the answers, but you would not question them. I don’t have data, but I would guess women were many of the typical users, in a patriarchal context where men probably spoke about things they didn’t know about with untouchable confidence (we still do), a woman using then encyclopedia would put a full stop to the conversation. My mom did, many times.

Around the year 2000 came the Wikipedia and it challenged the status quo of author-based knowledge creation, it started online as a collaborative, crowd sourced model, with the capability of being constantly updated. In 2005 Nature published a study comparing Wikipedia and Encyclopaedia Britannica, finding that Wikipedia’s accuracy was comparable, but as time passed and because of the disputed nature of the content, you could cite Wikipedia to resolve an argument, but whoever didn’t like what was written would always cite the accuracy and reliability of its content due to its open-edit model.

Now we are in the age of ChatGPT, while the Encyclopaedia had about 100,000 articles, Wikipedia has more than 6 million, and I have no idea if you can even count articles in ChatGPT due to its dynamic generation. The Encyclopaedia was done with experts and scholars, Wikipedia via community volunteers and ChatGPT has no fixed authors, it’s a concatenated amalgamation of everyone on the web. Interestingly, the accuracy of the Encyclopaedia was considered high, knowing that these experts and scholars were human beings and that “history is written by the victors”. These same experts and scholars are now less in favor, and we seem to trust more the type of result you get from a solution that at the bottom states “ChatGPT can make mistakes, Check important information”.

Nevertheless, I use ChatGPT often as an argument broker, I have a shared account with my wife, and we find ourselves using it as a place to discuss and evolve arguments where we start by recognizing we have different points of view. I may start a conversation with a question (trying not to ‘lead the witness’), she might follow up with her question, and then I follow-up after that, and most of the times we will end up in a place where we might be Ok with the conclusion. We use it almost as a third person in the debate, someone we ask in writing to be objective and impartial, we ask for sources, we ask for it to create summaries, to focus on what most important, most widely accepted, most asked and answered. Because we have had enough times where either one of us considers we won an argument via ChatGPT, we have not resorted yet to question or doubt it when it spells out something which is contrary to what we would have liked, we tend to go check the sources and try and understand how biased they are, but we have both learned new stuff and have landed in positions that are more understandable and data driven. We are both independent thinkers, and we don’t agree on many things, but we have agreed on this faulty tool to help us agree to disagree and go on with our lives.