Image © Jose 2025

I bought myself a $200 Black & Decker electric lawnmower. I know, like so many of us, I failed the “access over ownership” test. The 2010s popularized motto of the sharing economy – “you don’t need a drill, you need a hole in the wall” – didn’t catch on. The prices of renting versus owning are almost the same. Manufacturers created ecosystems that make it easier for the consumer to expand. And I think those behind this movement underestimated the emotional pull of personal identity tied to independence and home improvement.

It took me some time to investigate this, just because all power tools are becoming battery-operated, but I wasn’t sure this would make sense. First, because a decent battery-operated lawnmower costs over $600. And second, because I wasn’t sure batteries would pull it off.

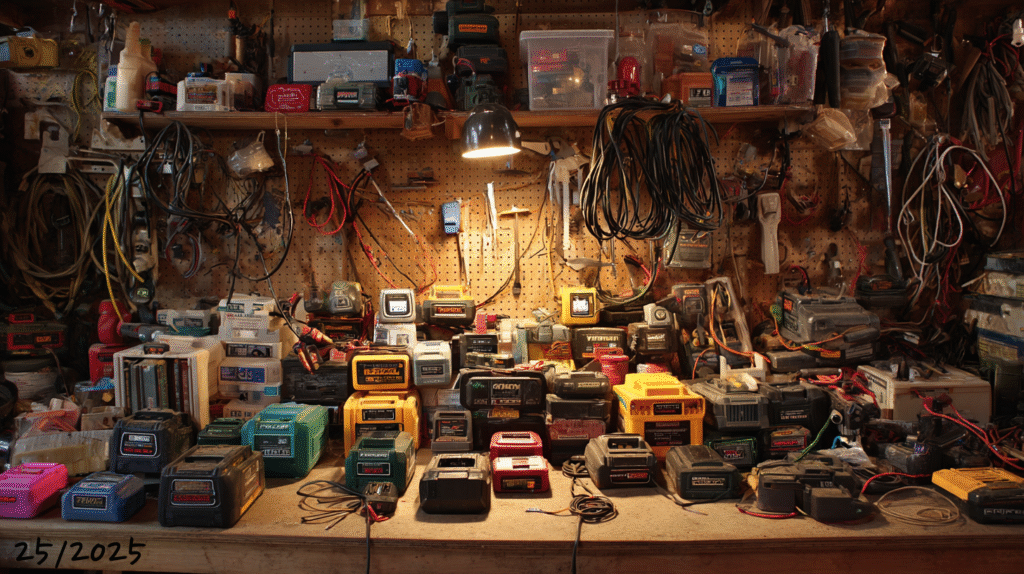

The U.S. cordless power tool trend began with Black & Decker in the 1960s but became commercially and professionally relevant in the 1980s–2000s, with Makita, Milwaukee, and DeWalt leading the shift to lithium-ion platforms. I’m aware there’s a dark side to the cordless power tool revolution, and it’s not just about batteries and branding, beneath the convenience and performance upgrades lies a systemic pattern of waste, exploitation, and erosion of repair culture that’s rarely acknowledged.

While I do have a few Makita tools, it pisses me off that they are changing (or “improving,” as they call it) their battery systems. I now have four batteries and a couple of chargers because different generation batteries require different types of chargers. I was looking into what Wirecutter had to say about this, and they recommend a brand I wasn’t aware of, EGO. They talk about its blend of clean cutting, runtime, self-propulsion, compact folding, and storage-friendly design making it a strong all-rounder. But you know what? That would take me to a different battery ecosystem. So, the brand strategy of using this as a preference seems to be working. The battery ecosystem in power tools has quietly become the new “walled garden” war. Very much like what Apple did in consumer electronics. It seems we’re no longer buying tools—we’re buying into ecosystems. And these ecosystems lock in, extract, and compete, just like iOS vs. Android or Mac vs. PC. But I started thinking about how much grass I really have to mow, and how many times I’ll actually be doing this. So, I decided to go with an electric, cable-operated lawnmower. I do need a long extension cord, and the mowing itself requires a bit more dancing around the cable, but for now, this is fine.

Then I was looking into the equipment as an industrial designer. The product and the experience of this lawnmower is mehhh, but does the job. Above all, I was looking at how can it be that this only costs $200.

I understand economies of scale, and when you blow up the bill of materials of a product such as this, you start to see how the cost might be around $90. The motor and the plastic parts each cost around $25. Add to this another $20 for logistics and import costs (all made in China), and a typical brand markup of 30–50%, you end up with a wholesale price of $140. The whole thing, in this product but also in the more expensive solutions, seems to be around perception of quality and performance, made through plastic parts and trims, design at work to differentiate products that would otherwise be very hard to tell apart in the marketplace.

For many years, designers have talked about changing these ecosystems. We talked about modularity, repairability, interoperability, shared use. But most efforts failed to understand how people actually think and feel about tools, about ownership, about what it means to fix something yourself. Meanwhile, brands told better stories, they created habits, they built ecosystems that rewarded loyalty, simplified decision-making, and gave people the feeling of capability, even when the systems around them were locking them in.

I’m not throwing in the towel. I still believe in design as a force for better. But maybe we’ve been focusing too much on the tool, and not enough on the world around the tool. On the incentives. On the mental models. On the deeper reasons people prefer to own rather than borrow, to buy into a system rather than remain brand-agnostic. Maybe it’s time we grow up as a discipline, and start designing with power, and systems thinking.

This $200 lawnmower might not save the planet. But it’s a small reminder that the real design challenge isn’t always the product. It’s the ecosystem it’s born into, and the behaviors we help shape around it.

Comments

Powered by WP LinkPress